Understanding why your habits are failing is the first step toward correcting your strategy and achieving real change.

You’ve tried before. You downloaded the app, bought the new workout gear, and filled your fridge with healthy food. For a week, maybe two, you were a model of discipline. You woke up early, you meditated, you journaled, you avoided sugar. You ran on pure, unadulterated willpower. And then, one Tuesday, it all fell apart. A stressful day at work led to a pizza, which led to skipping the morning workout, which led to the journal gathering dust on your nightstand.

If this story feels familiar, you are not alone. And more importantly, you are not a failure. The problem isn’t your lack of willpower; it’s the strategy. Relying on sheer determination to forge new behaviors is like trying to hold back a river with your bare hands. It might work for a moment, but eventually, you’re going to get tired. This is especially true for those of us living in busy, urban environments, where our senses are constantly bombarded with temptations, distractions, and demands on our energy.

Every billboard, every notification, every conveniently located fast-food restaurant is a carefully engineered attack on your focus and resolve. In this environment, willpower is a finite resource that gets depleted with every decision you make. By the end of the day, you have none left to fight the urge for takeout and Netflix. So, what’s the alternative? How do you create meaningful change that sticks?

The key to building habits that last isn’t about grand, heroic acts of self-control. It’s about something much quieter, gentler, and infinitely more powerful: understanding the architecture of your own behavior and making tiny, consistent, almost effortless changes. It’s about building systems that support your goals, so you don’t have to rely on a resource as fickle as willpower. This guide will walk you through a realistic, compassionate approach to long-term habit building. We will explore how to design your life in a way that makes good habits the easy choice and bad habits the difficult one. Forget the burnout cycle. It’s time to build habits that last forever, one tiny step at a time.

📚 Table of Contents

- Understanding the Engine: The Science of How Habits Work

- Designing Your Environment for Effortless Success

- Start Absurdly Small: The Minimum Viable Action

- The Friction Audit: Make Good Habits Easy and Bad Habits Hard

- Let Your World Be Your Guide: Engineering Cues

- The Power of Stacking: Linking New Habits to Old Ones

- Building Resilience: How to Handle Setbacks and Stay Consistent

- The “Never Miss Twice” Rule: Your Relapse Plan

- Streaks Aren’t Everything: Resetting Without Shame

- Gentle Accountability: Sharing Your Process, Not Just Your Results

- Putting It All Together: Two Sample Routines

- The Evening Wind-Down: A Routine for Better Sleep

- The Morning Focus Primer: A Routine for a Productive Day

- Frequently Asked Questions About Long-Term Habit Building

- How long does it really take to form a new habit?

- What should I do when I travel or my routine is disrupted?

- I was making great progress, but now I’ve hit a plateau. What’s wrong?

- Can I try to build multiple new habits at the same time?

- Your First Steps to Building Habits That Last

Understanding the Engine: The Science of How Habits Work

Before we can build new habits, we need to understand how they operate. Think of a habit as a mental shortcut. Your brain is an efficiency machine; it loves to automate repetitive tasks to save energy for more complex problems. When you first learn to drive, every action is deliberate and requires immense focus. But after years of practice, you can drive home from work while thinking about dinner, barely conscious of the hundreds of micro-decisions you’re making. That’s the power of a habit. It’s a behavior that has become so automatic it happens almost without your conscious permission.

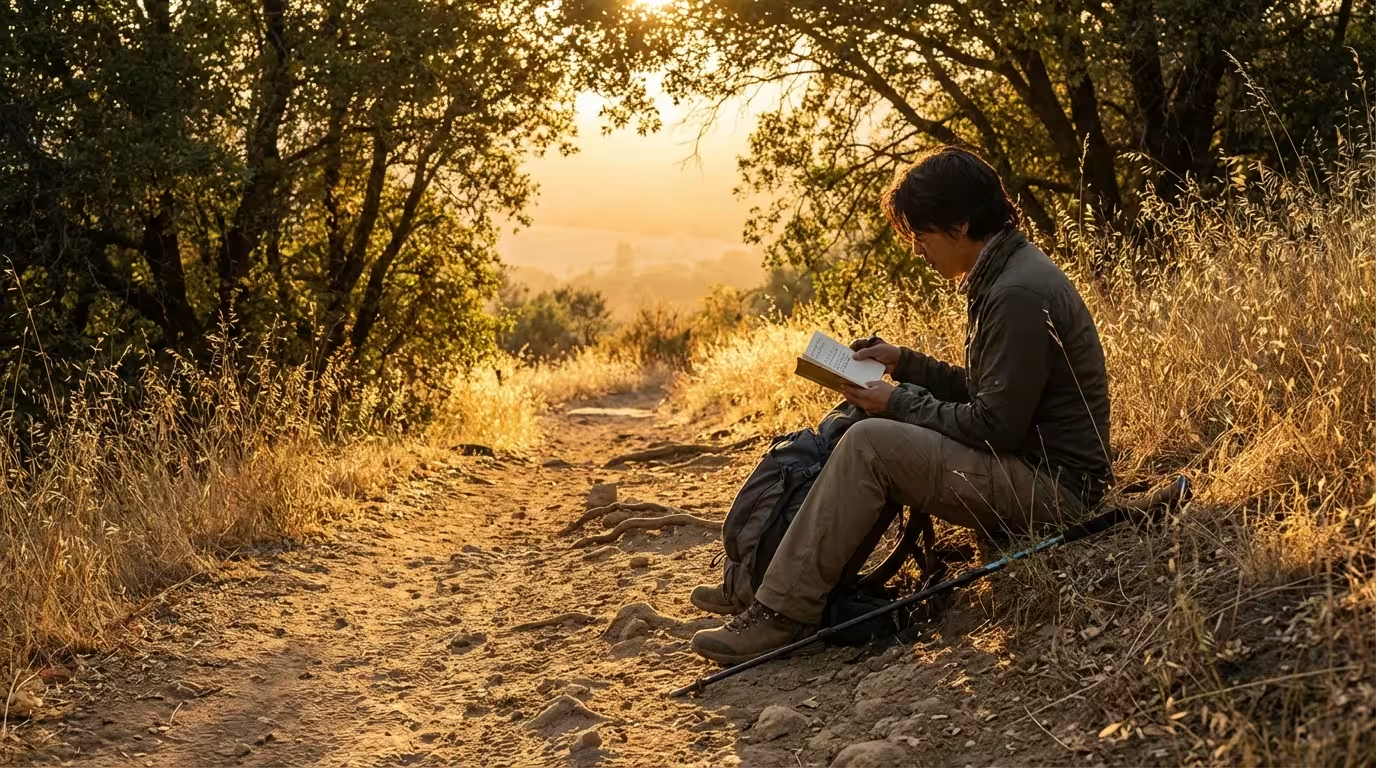

While we often blame a lack of willpower, understanding why your brain fights change is the first step in bypassing its natural resistance to new routines.

This automation process is governed by a simple neurological pattern that scientists, including many supported by research from institutions like the National Institutes of Health (NIH), have identified. We can break it down into a simple, three-part framework.

The Simple Loop: Cue, Action, Reward

At the core of every habit is the habit loop. It’s a straightforward cycle that consists of three components: the cue, the action, and the reward. Understanding this loop is the first step in deconstructing your existing behaviors and designing new ones.

1. The Cue: This is the trigger, the spark that tells your brain to initiate a certain behavior. A cue can be anything. It could be a time of day (7:00 AM), a location (your kitchen), an emotional state (feeling stressed), a preceding action (finishing dinner), or the presence of other people. When your phone buzzes (cue), you automatically reach for it (action).

2. The Action: This is the habit itself—the actual behavior you perform. It can be a physical action, like grabbing a cookie, or a mental one, like worrying about a future event. It’s the routine your brain runs when prompted by the cue.

3. The Reward: This is the satisfying outcome that tells your brain, “Hey, this sequence was worth remembering for the future.” The reward is what closes the loop and solidifies the habit. For checking your phone, the reward might be a hit of social connection or a moment of distraction from a boring task. For eating a cookie, it’s the delicious taste of sugar. The more immediate and satisfying the reward, the more strongly the brain learns to associate the cue with the action.

Every habit you have, good or bad, follows this pattern. Feeling tired in the afternoon (cue) leads to drinking a cup of coffee (action), which results in a feeling of alertness (reward). By identifying the loops that govern your life, you gain the power to change them. You can’t easily eliminate a cue, but you can change the action that follows it.

Beyond Goals: The Power of Identity-Based Habits

Now that we understand the mechanics of a habit, we need to address the motivation behind it. Many of us approach habit building with an outcome-based mindset: “I want to lose 20 pounds,” or “I want to write a novel.” While these goals are great for setting a direction, they are often poor motivators for daily action. When you focus only on the outcome, you are in a constant state of pre-success failure. Every day you haven’t lost 20 pounds feels like you haven’t succeeded yet.

A more powerful and sustainable approach is to focus on identity-based habits. This means shifting your focus from what you want to achieve to who you wish to become. The goal isn’t to run a marathon; it’s to become a runner. The goal isn’t to write a book; it’s to become a writer. The goal isn’t to meditate for 30 minutes; it’s to become a calm and mindful person.

This small shift in perspective is profound. Every action you take becomes a vote for the type of person you want to be. When you choose to go for a jog, even a short one, you are casting a vote for “I am a runner.” When you write one paragraph, you are casting a vote for “I am a writer.” These small wins build up evidence of your new identity. You’re not just chasing a distant goal; you’re reinforcing who you are in the present moment.

This approach makes long-term habit building much more resilient. When your motivation wanes, you’re not just failing to meet a goal; you’re acting out of alignment with your identity. And that internal friction is a powerful motivator to get back on track. So, before you decide on a new habit, ask yourself: “Who is the person I want to become?” Then, start taking small actions that prove that identity to yourself.

Designing Your Environment for Effortless Success

The most successful people don’t have more willpower than you; they have better systems. They understand that human behavior is a product of its environment, and they intentionally design their surroundings to make their desired actions easier and their undesired actions harder. This is the practical core of building habits that last. It’s about shifting the burden from your internal discipline to your external world. Let’s explore four powerful strategies for designing an environment that does the heavy lifting for you.

Start Absurdly Small: The Minimum Viable Action

One of the biggest mistakes we make when starting a new habit is making it too big. We declare, “I’m going to work out for an hour every day!” This initial burst of enthusiasm is great, but it’s not sustainable. On a busy or low-energy day, the sheer scale of that commitment feels overwhelming, and so we do nothing at all. The key is to start with something so easy that you can’t say no.

This is the concept of a minimum viable action. It’s the smallest possible version of your desired habit, an action that takes less than two minutes to complete. The goal is not to get a result on day one; the goal is to show up and cast a vote for your new identity.

Instead of “read a chapter every night,” your minimum viable action is “read one page.” Instead of “meditate for 20 minutes,” it’s “sit and breathe for 60 seconds.” Instead of “go for a 3-mile run,” it’s “put on your running shoes and step outside.”

This may sound ridiculously simple, but its effect is profound. A minimum viable action removes the friction of starting. Once you’ve read one page, you might feel like reading a few more. Once you’ve put on your running shoes, you might as well go for a short walk. But even if you don’t, you’ve still succeeded. You showed up. You maintained the chain of consistency, which is the most critical factor in the early stages of habit building. You can always scale up later, once the behavior has become automatic.

The Friction Audit: Make Good Habits Easy and Bad Habits Hard

Every action you take has a certain amount of friction associated with it—the physical and mental effort required to perform it. To build good habits, you must decrease the friction. To break bad habits, you must increase it. Take 30 minutes to conduct a friction audit of your life.

To decrease friction for good habits, ask: “How can I make this ridiculously easy to start?”

If you want to exercise in the morning, lay out your workout clothes the night before. If you want to drink more water, fill up a large water bottle and place it on your desk. If you want to practice guitar, take it out of its case and put it on a stand in the middle of your living room. Reduce the number of steps between you and the desired action.

To increase friction for bad habits, ask: “How can I make this inconvenient to do?”

If you watch too much television, unplug it after each use and put the remote in another room. If you snack on junk food, store it in an opaque container on a high shelf, or better yet, don’t buy it in the first place. If you waste time on your phone, delete social media apps and only access them through the slower mobile browser. Add steps, time, and effort between you and the behavior you want to avoid. This small amount of friction is often enough to make you pause and reconsider, giving your rational brain a chance to intervene.

Let Your World Be Your Guide: Engineering Cues

As we learned from the habit loop, every habit starts with a cue. Most of the cues in our lives are accidental. We see a plate of cookies on the counter and suddenly feel the urge to eat one. We hear a notification and instinctively check our phone. But what if we designed our cues intentionally? Your environment can be a powerful ally in your long-term habit building journey if you make your desired cues obvious and visible.

Want to floss every night? Put the floss container directly on top of your toothpaste. The toothpaste becomes the visual cue. Want to take a vitamin every morning? Place the bottle right next to your coffee machine. The act of making coffee becomes the cue. Want to practice a new language? Leave the textbook open on the chair where you have your morning coffee. By embedding these triggers into your environment, you offload the responsibility of remembering from your brain to the world around you. Your environment becomes your personal coach, gently nudging you toward your goals throughout the day.

The Power of Stacking: Linking New Habits to Old Ones

One of the most effective ways to introduce a new habit is to piggyback it onto an existing one. This strategy is called habit stacking. You already have dozens of robust, automatic habits you perform every day without thinking: waking up, brushing your teeth, making coffee, getting dressed, commuting. These are solid anchor points on which you can attach a new behavior.

The formula is simple: “After [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW HABIT].”

For example: “After I pour my morning cup of coffee, I will sit and meditate for one minute.” “After I take off my work shoes, I will immediately change into my workout clothes.” “After I brush my teeth at night, I will write down one thing I’m grateful for.”

The beauty of habit stacking is that the existing habit acts as a powerful, reliable cue. You don’t need a new reminder because the new behavior is directly linked to a routine that is already deeply ingrained in your brain. This makes the new habit feel like a natural extension of your existing flow rather than a completely new, isolated task you have to force yourself to remember.

![]()

Building Resilience: How to Handle Setbacks and Stay Consistent

The path to building habits that last is not a straight line. It’s a messy, human process filled with missed days, waning motivation, and unexpected life events. The difference between someone who succeeds and someone who gives up is not that the successful person never fails; it’s that they have a plan for failure. They know how to get back on track quickly and compassionately. Building resilience into your habit-building process is just as important as designing the habits themselves.

Beyond mental toughness, you can learn how to make your habits habit-proof against relapse by preparing for specific high-stress triggers.

The “Never Miss Twice” Rule: Your Relapse Plan

Perfectionism is the enemy of progress. If your goal is to be perfect, a single slip-up can feel catastrophic. You miss one workout, and your brain tells you, “See? I knew you couldn’t do it. The whole week is ruined. You might as well give up and start again next Monday.” This all-or-nothing thinking is a common trap that derails countless well-intentioned efforts.

A much more effective and compassionate mantra is the “never miss twice” rule. Life happens. You will get sick, you will have to work late, you will have days where you are exhausted and just don’t have it in you. It is inevitable that you will miss a day. That’s okay. The key is to not let one missed day turn into two. Missing once is an accident. Missing twice is the start of a new, undesirable habit.

Your goal is simply to get back on track at the next available opportunity. If you miss your morning workout, do a few push-ups before bed. If you eat an unhealthy lunch, make sure your dinner is nutritious. The point is to stop the downward spiral before it begins. One bad meal doesn’t make you an unhealthy person, just as one missed workout doesn’t erase all your progress. Forgive yourself for the slip-up and focus all your energy on simply showing up the next time. This approach maintains your momentum and reinforces the identity you are trying to build, even on imperfect days.

Streaks Aren’t Everything: Resetting Without Shame

Habit-tracking apps have made the concept of “streaks” incredibly popular. Seeing a long chain of X’s on a calendar can be a powerful motivator. It provides a visual representation of your consistency and can make you want to keep the chain going. However, this psychology has a dark side. When you inevitably break a 100-day streak, the feeling of loss can be so demotivating that it causes you to quit altogether.

While streaks can be useful, it’s crucial not to become a slave to them. The goal is not a perfect streak; the goal is to be the type of person who consistently engages in a certain behavior. A 98% success rate over a year is far more valuable than a perfect 100-day streak followed by 265 days of nothing. When a streak breaks, don’t let shame or disappointment take over. Acknowledge it, perhaps reflect on why it happened, and then immediately start a new streak of one. The most important day is today.

Think of it like this: if you were driving to a destination and took a wrong turn, you wouldn’t just abandon the car and walk home. You would simply correct your course and keep driving. Treat your habits the same way. A broken streak is just a wrong turn. Acknowledge it, reset your focus, and keep moving toward the person you want to become. This is the essence of sustainable habit building.

Gentle Accountability: Sharing Your Process, Not Just Your Results

Accountability can be a powerful tool for staying on track, but it needs to be handled with care. Often, we think of accountability as having someone who will scold us if we fail. This can create a dynamic of fear and shame, which are not effective long-term motivators. A gentler, more supportive form of accountability is to find a partner or group with whom you can share your process.

This isn’t about announcing your grand goals to the world, which can sometimes give you a premature sense of accomplishment. Instead, find one trusted friend and agree to a simple, daily check-in. It could be a quick text that says, “Done” or “Missed today, but will be back at it tomorrow.” Knowing that someone is expecting to hear from you can provide just enough positive social pressure to help you follow through on days when your motivation is low.

The key is to find someone who is supportive and non-judgmental. The goal is not to impress them but to have a partner in the process. This creates a sense of shared journey and normalizes the ups and downs of long term habits. You’re not alone in your struggles, and you have someone to celebrate your small wins with, which can make the entire process more enjoyable and sustainable.

Putting It All Together: Two Sample Routines

Theory is useful, but seeing these principles in action can make them much clearer. Let’s walk through how to design two simple but powerful routines using the concepts of identity, cues, minimum viable actions, and habit stacking. These are just examples; the goal is for you to use the same thinking to build routines that fit your own life and goals.

The Evening Wind-Down: A Routine for Better Sleep

Let’s say your goal is to improve your sleep. The identity you want to embody is: “I am a person who rests well and values my health.” Your current habit loop might be: feeling tired after dinner (cue) leads to scrolling on your phone or watching TV in bed (action), which provides a reward of easy entertainment but ultimately harms your sleep quality. We need to design a new routine.

First, we’ll use habit stacking. The anchor habit will be finishing the dinner dishes. The stack will look like this: After I put the last dish away, I will immediately change into my pajamas. This simple act is a powerful cue that signals the transition from the busy part of the day to the relaxation phase. Next, we apply a minimum viable action. Instead of a vague goal like “read more,” the action is: After I change into my pajamas, I will sit in my reading chair and read one page of a physical book. Just one page. It’s so easy you can’t say no. Finally, we manage friction. We increase friction for the bad habit by leaving the phone charger in the living room overnight, far from the bedroom. We decrease friction for the good habit by placing the book and a cup of herbal tea on the nightstand in the afternoon, making the new routine inviting and easy to start. This new loop replaces mindless scrolling with a calming ritual that directly supports your identity as someone who rests well.

The Morning Focus Primer: A Routine for a Productive Day

Now, let’s design a routine to start the day with intention. The identity here is: “I am a focused and proactive person who controls my day; my day does not control me.” The common, reactive habit loop is: the alarm goes off (cue), you grab your phone (action), and you are immediately flooded with emails, news, and notifications (a stressful reward that hijacks your attention). We want to build a better system.

Our anchor habit will be turning off the alarm. The habit stack begins: After I turn off my alarm, I will not look at my phone. I will immediately walk to the kitchen and drink a full glass of water. This first step rehydrates you and gives you a moment to wake up. Next, another stack: After I drink my glass of water, I will sit down at the kitchen table with a notebook and pen. Here comes the minimum viable action: I will write down one priority for the day. Just one. This simple act shifts your brain from a reactive mode to a proactive one. You have defined your own agenda before the world has had a chance to define it for you. To make this work, we manage friction. The night before, you place the glass, notebook, and pen on the kitchen table. You also enable a “do not disturb” mode on your phone that lasts until 30 minutes after you wake up, adding a layer of friction to the habit of checking it first thing.

These routines aren’t about adding more to your plate. They are about using small, intelligent changes to a few key moments to set a positive trajectory for the rest of your day or night, reinforcing your desired identity every step of the way.

Frequently Asked Questions About Long-Term Habit Building

As you embark on your journey of building better habits, questions and obstacles will naturally arise. Here are answers to some of the most common challenges people face when trying to make habits that last.

How long does it really take to form a new habit?

You may have heard the popular myth that it takes 21 days to form a habit. While a catchy number, research shows it’s much more variable. A landmark study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology found that, on average, it takes about 66 days for a new behavior to become automatic. However, the range was huge—from 18 days to 254 days—depending on the person, the behavior, and the circumstances. The lesson here is to be patient with yourself. Don’t fixate on a magic number. Focus on consistency, not a deadline. The goal is to make progress, not to achieve perfection in three weeks. True long-term habit building is a marathon, not a sprint.

What should I do when I travel or my routine is disrupted?

Disruptions like travel, holidays, or illness are one of the main reasons habits fall apart. The key is to have a flexible plan. Don’t adopt an all-or-nothing mindset. Instead, scale your habit down to its absolute minimum viable action. If your habit is to do a 30-minute workout at your home gym, your travel version might be to do 5 minutes of bodyweight exercises in your hotel room. If you write 750 words a day, your vacation version might be to write a single sentence in a journal. The goal during a disruption is not to make progress, but to maintain the identity. You are still a person who exercises; you are still a writer. By performing a tiny version of your habit, you keep the thread of consistency alive, making it infinitely easier to ramp back up to your normal routine when you return.

I was making great progress, but now I’ve hit a plateau. What’s wrong?

Plateaus are a normal and expected part of any long-term process. They don’t mean you’re doing something wrong. Often, a plateau is a sign that your brain and body have adapted to the current level of challenge. The initial excitement has worn off, and the habit is now simply part of your routine. This is actually a sign of success! However, if you want to continue making progress, you may need to introduce a new, small challenge. If you’ve been meditating for 2 minutes every day, try increasing it to 3. If you’ve been running the same 2-mile route, try a slightly hillier path. The principle of progressive overload, often discussed in fitness, applies to many habits. Make a small, 5% adjustment to keep things interesting and continue your growth. But remember, it’s also perfectly fine to maintain a habit at a comfortable level. Not every habit needs to be constantly escalated.

Can I try to build multiple new habits at the same time?

While it’s tempting to overhaul your entire life at once, it’s generally a recipe for burnout. As we’ve discussed, even small changes require mental energy and focus at the beginning. Trying to build several major habits simultaneously—like starting a new diet, a new workout routine, and a daily writing practice all on the same day—divides your focus and depletes your willpower too quickly. A more sustainable approach is to focus on one, or at most two, key habits at a time. Once the first habit becomes relatively automatic (after a couple of months), you can then use your renewed focus and the confidence from your success to begin building the next one. Using habit stacking can be a way to gently introduce a very small second habit that is linked to your primary new one, but be cautious about taking on too much too soon.

Your First Steps to Building Habits That Last

You now have the framework and the tools for a more compassionate and effective approach to habit building. You understand the power of identity, the mechanics of the habit loop, and the importance of designing your environment for success. The journey from knowledge to action is the most important one you can take. It’s not about a massive, life-altering change tomorrow. It’s about a tiny, almost insignificant step today.

This is not a race. This is the patient, deliberate process of becoming the person you want to be. It’s about trading short-term intensity for long-term consistency. The path to building habits that last is paved with small, repeated actions that accumulate into remarkable transformations over time. You have the capacity for incredible change within you. The key is to unlock it gently.

Here are three simple actions you can take in the next seven days to begin your journey:

1. Choose One Keystone Habit. Don’t try to change everything at once. Pick one single area you want to improve. Ask yourself, “What one habit would have the most positive ripple effect in my life?” This could be related to your health, your work, or your relationships. Define the identity associated with it (e.g., “I am a person who moves their body every day”).

2. Define Your Minimum Viable Action. Based on your chosen habit, what is the absolute smallest version you can do? The two-minute version. If your habit is to read more, commit to reading one page. If it’s to keep your home tidy, commit to putting away one item that is out of place. Write this minimum viable action down.

3. Stack It and Remove Friction. Identify a strong, existing habit in your daily routine to act as your cue (like brushing your teeth or making coffee). Use the “After [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW MINIMUM VIABLE ACTION]” formula. Then, take five minutes to remove one piece of friction. Lay out your book, put your running shoes by the door, or place a water bottle on your desk. Make it obvious and easy to begin.

Commit to just these three steps. Focus only on showing up and performing your tiny habit for one week. See how it feels. You might just be surprised at how a small, consistent effort can be the beginning of a change that lasts a lifetime.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for informational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for professional medical or psychological advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or mental health.

For expert guidance on productivity and focus, visit Mindful.org, American Psychological Association (APA), Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP) and Getting Things Done (GTD).

Establishing a clear plan to combat habit slippage ensures that one bad day doesn’t turn into a permanent break in your routine.

Leave a Reply